Expert Expressions

Dr C.P. Rajendran

The writer is an adjunct professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, and author of a forthcoming book, Earthquakes of the Indian Subcontinent.

Built at the site of an infamous detention centre set up by the British government, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)- Kharagpur was the first to be commissioned among the four premier higher technical institutes. Jawaharlal Nehru who gave a memorable convocation address at IIT-Kharagpur in 1956, made a prophetic statement: "Here in the place of that Hijli Detention Camp stands the fine monument of India, representing India's urges, India's future in the making. This picture seems to me symbolical of the changes that are coming to India." Notwithstanding the criticism of encouraging brain drain and that they generated an intense admission competition among the school-going students leading to the entrenchment of an unhealthy tuition culture in the country, the premier IITs continue to have a transformative presence in our technical and science education system. Nehru was indeed right in saying that it was the Indian future in the making. Strangely, the IIT Kharagpur is currently in the news - not for its role in shaping the future but for distorting our past by practising the art of historical revisionism to advance a particular social agenda.

In the pretext of generating a calendar for the year 2022, its new Centre, purportedly created for the studies of Indian Knowledge Systems, conveniently used it as a platform for propagating an unscientific narrative on the beginnings of our ancestry. Titled as “Recovery of the Foundation of Indian Knowledge Systems”, this calendar presented a very confusing, often unrelated collage of symbols and images with patently distorted ideas in its twelve pages. The intention of the calendar is to establish an alternate premise that the Aryans - the carriers of Vedic culture - were indigenous to the Indus River Valley and surrounding region. This premise advances the theme that these people were the custodians of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC; known also as the Harappan) that had been active for more than 10000 years, eventually spreading its cultural influence westwards from India. This is called the ‘out of India’ theory that there was only decline followed by a resurgence resulting in the export of an archaic form of Sanskrit – the sacerdotal language used for chanting of Vedas.

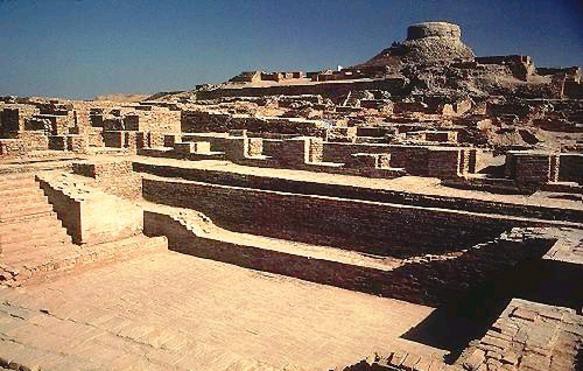

As the historian Charles Allen stated in his book, such revisionism flies in the face of all the evidence- archaeogenetics, archaeological, linguistic, zoological, botanical, geographical and theological. The evidence informs us that the pre-Indian state’s civilizational beginnings are associated with the Harappans, the earliest settlers and belonging to a greater IVC, whose culture extends from 7,000 to 2,000 BC. The remnants of their settlements are located over a wide area around the Indus River, Kutch, Saurashtra and the parts of Balochistan and Makran Coast. Engaged in agriculture and trade, they were adept at designing well-laid out townships with a refined taste for water management. They used bullock-drawn carts and were unaware of horse-drawn chariots. Predominantly centred on farming, these communities slowly declined as a result of climatic changes in the form of increasing aridity and declining summer rainfall.

The archaeological evidence also suggests that during the late Harappan period, the Rigvedic people entered the Indian subcontinent through present-day Iran and Afghanistan. These pastoral migrants and their grazing animals including horses came in from the Eurasian steppes into the Indus Valley region, in batches to mingle with the dark-skinned settlers of the Indus Valley. Although not an ‘invasion’ in the classical sense, as the American archaeologist George Dales had noted, “Harappans met their end not with an Aryan bang, but with an Indus expatriate’s whimper”, borrowing a figure of speech from T.S. Eliot. But the ‘in-group-out-group’ dynamics that may have played out in such a cultural landscape may have encouraged caste-based social hierarchy, allowing the socially resourceful newcomers to dominate and for the earlier settlers to have become marginalised, forcing them to migrate possibly southwards. The results of excavations from Keezhadi in Tamil Nadu provide further evidence of continued extended spread of the non-Vedic culture towards south India until 2200 years ago.

The recent archaeo-genetic studies provide us a firmer scientific foundation to the theory of Aryan migration from the Eurasian steppes. For instance, the mitochondrial DNA (designated haplogroup R1a1a) of some of the social groups in India share a common genetic ancestral lineage with eastern Europeans. It is suggested that haplogroup R1a1a mutated out of haplogroup R1a in the Eurasian Steppe about 14,000 years ago. Thus, these studies support the ‘Out of the East European Steppes’ theory. It also means that the original form of Indo-European languages was first spoken in Eastern Europe, the ‘original’ homeland. It is likely that a group of nomads that shared the genomic subclade R1a1a left their homeland and moved east towards the Caspian grasslands, where they tamed horses, goats and dogs and learned to build horse-drawn chariots, essential for a nomadic life. Around 1,900 BC, these people broke up and one group proceeded to what is now Iran, and the other into India. Those who entered India, around 1,500 BC, established the dominant civilization in Northwestern India. By then, much of the older Harappan settlers had either become marginalised or had moved to the south and central India, and even to parts of Balochistan. The newly settled people, the so-called ‘Aryans’ themselves, who worshipped fire, were not builders like the Harappans but are likely to have been better story-tellers.

Two recently published scientific papers, reporting the archaeo-genomic studies of the early settlers of central and south Asia. They chart the genetic trail of the hunter-gatherers, Iranian farmers and pastoralists from the Caspian steppes, and how they may have intermingled to become the makers of some of the world’s earliest civilizations. Obtained from a skeleton of a woman from a 5000-year old IVC settlement in the village of Rakhigarhi, in the Hisar District of Haryana, the companion paper tracks the lineage of the people who settled in the Indus Valley. The DNA from the skeleton shows no detectable ancestry from the “steppe pastoralists or from Anatolian and Iranian farmers, suggesting farming in South Asia arose from local foragers rather than from large-scale migration from the west”. This conclusion, with a caveat that a single sample cannot fully characterise the entire population, reinforces the prevailing notion on origins of the Harappan settlers. It is also likely that there could be more genetic commonality between much earlier settlers from Africa and Harappan people.

The January page of the IIT calendar starts with a statement, “the tributaries of Indus as mentioned in the Rig Veda are sourced to the Siwalik ranges in the Central-Eastern Himalayas”. The Siwaliks are the low-altitude southern-most hill ranges of the Himalaya from where no major rivers are sourced. If this is not a deliberate distortion for the ease of false messaging, this apparent lack of geographical understanding for those who are pioneering the studies of Indian Knowledge Systems is shocking, to say the least. That the calendar makers resorting to obfuscation of facts becomes obvious also in the succeeding pages. For instance, as Meera Nanda pointed out, the fact that ‘Karmic’ retribution and idea of rebirth, as implied in Calendar’s February page are not part of early Vedic tradition, but derived from the Buddha-Jaina streams of thought that was later incorporated in the Upanishads and finds its philosophical exuberance in Adi Shankara’s oeuvre in the 8th century CE.

Leave a comment