Much has happened in the interval that separates us from James Watson, who, by inventing the steam engine in 1784 formally marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and the world’s first fossil-fuel economy. If the Anthropocene epoch had begun by now, the revolution heightened its fervour, anticipating the emergence of modern human society.

In the early 20th century, the Russian geoscientist Vladimir Vernadsky had the foresight in his books to define the “anthropogenic era”, but in a rather celebratory tone. Vernadsky was a product of his times but also wore an exaggerated technological optimism – a key characteristic of Soviet Marxism – and likely believed in the ultimate triumph of the “Soviet man” over nature.

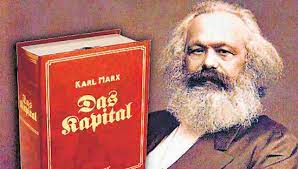

Today, a new generation of thinkers are highlighting strands of ecological thought in Karl Marx’s work that their predecessors had set aside. On the rift between ecological stability and the capitalist growth, Marx draws on the pioneering research of the German chemist Justus von Liebig to discuss the process by which capitalism tends to deplete soil fertility in Das Kapital: “Capitalist production, by collecting the population in great centers, and causing an ever-increasing preponderance of town population, on the one hand concentrates the historical motive power of society; on the other hand, it disturbs the circulation of matter between man and the soil, i.e., it prevents the return to the soil of its elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; it therefore violates the conditions necessary to lasting fertility of the soil.”

The soil depletion crisis reflects Marx’s fundamental conception of the ‘metabolic rift’. To quote the sociologist John Bellamy Foster, the metabolic rift “concerns the interplay between the degradation of the environment and human development in ways not accounted for in standard economic metrics like GDP”.

The ecological concerns in Marx’s writing were motivated principally by an environmental problem that ravaged Europe and North America in the mid-19th century, the result of intensive farming and rapid urbanisation leading to the depletion of soil nutrients. Reminiscent of India’s current agricultural crisis due to the migration of labour, mid-18th century Europe saw an exodus of people to cities, drawn there by the promises of industrialisation, throwing up the twin problems of massive sewage build-up in urban centres and nutrient depletion in the soil in the countryside. As Marx wrote (vol. 3): “Excretions of consumption are of the greatest importance for agriculture. So far as their utilization is concerned, there is an enormous waste of them in the capitalist economy. In London, for instance, they find no better use for the excretion of four and a half million human beings than to contaminate the Thames with it at heavy expense.”

In its quest to maintain profits, the 19th-century British state took to some quick fixes, like raiding Sicilian catacombs and Napoleonic battlefields for bones to use as fertilisers; it even tried transporting deposits of bird excreta, called ‘guano’, from Peru. These frantic and unsustainable bids, often brutally exploiting slave labour, only drove the seabirds away and accelerated the depletion of guano. This in turn affected the livelihoods of the Peruvian Indigenous peoples, who had been using it as a natural fertiliser in a sustainable way. The imperial powers solved their soil depletion crisis only with the advent of chemical fertilisers, which remain with us to this day – and which today’s farmers often blame for being detrimental to soil nutrients, ecology and the groundwater. History repeats itself.

Since Marx wrote Kapital in the 19th century, the global economy is five-times as big as it was half a century ago (on average) and is expected to be 80-times as big by 2100. The consequences of such an exponential rise in economic productivity have been piling up since the Industrial Revolution, and have already degraded more than 60% of the world’s ecosystems. In 2009, the world’s leading Earth-system scientists introduced the ‘planetary boundary’ frameworks that delineated safe spaces for human activities, and they are all being transgressed today. This reality compelled the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (a.k.a. IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Science-policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services to recommend degrowth measures to mitigate climate-related hazards and biodiversity loss.

However, none of the countries that participated in discussions on these reports wanted to address the issue of endless growth. Politicians don’t want to upset the apple cart, however dire the situation, and admit the fact that nearly half the planet lives on less than $5 (Rs 407) a day. The dominant growth model has failed the ecological systems that are crucial for our survival. The benefits of wanton growth have only accrued to a fifth of the world’s people, leaving our societies to confront the Siamese twins of climate change and increasing inequality. The votaries of Keynesian economic theory believe that we can grow our economies as well as reverse environmental degradation using techno-fixes – a belief at odds with reality. From the indications that are available now, we risk a collapse of the Earth-system if we continue on the path of ‘business as usual’.

One of the strongest critiques on the current growth model came from a 1972 report entitled ‘The Limits to Growth’, prepared by a group of economists led by Donella Meadows. The report questioned the foundations of industrial society against the biophysical limits of earth and exponential population growth. Ecological economists like Tim Jackson have called for an alternative approach. Both these and other tacks ask people to give up the notion of the ‘gross domestic product’ (GDP) as a financial goal because it thrives on unlimited consumerism. Instead, they call on countries to develop other macroeconomic models that combine economic, financial, social, and ecological variables.

The 2008 economic crisis, the ongoing one attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and an impending recession all indicate that growth predicated on consumerism is not sustainable. One day, the bill will come due. And as the traditional Left appears to lack imagination and refuses to leave its comfort zone, India requires new political spaces and social movements if it is to bring degrowth alternatives into the public consciousness, and promote cross-disciplinary research on ‘green economic models’ tailored to India’s conditions. As Marx declared in Kapital: “Even an entire society, a nation, or all simultaneously existing societies taken together, are not owners of the earth. They are simply its possessors, its beneficiaries, and must bequeath it in an improved state to succeeding generations as boni patres familias (good heads of the household).”

We need to learn from the planetary ecological crisis and replace consumerism and the domination of nature with, in Foster’s words, “quality of life, human solidarity and ecological sensibility”.

Leave a comment